A new text by Prof. Matteo Pasquinelli for e-flux journal #101

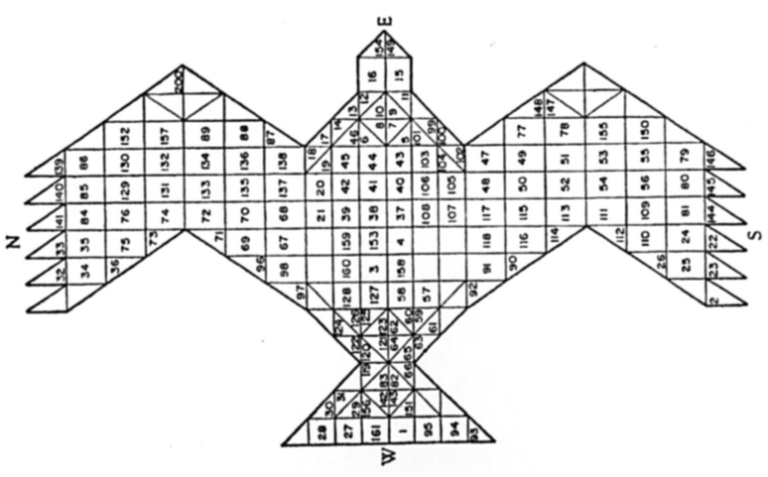

In a fascinating myth of cosmogenesis from the ancient Vedas, it is said that the god Prajapati was shattered into pieces by the act of creating the universe. After the birth of the world, the supreme god is found dismembered, undone. In the corresponding Agnicayana ritual, Hindu devotees symbolically recompose the fragmented body of the god by building a fire altar according to an elaborate geometric plan. The fire altar is laid down by aligning thousands of bricks of precise shape and size to create the profile of a falcon. Each brick is numbered and placed while reciting its dedicated mantra, following step-by-step instructions. Each layer of the altar is built on top of the previous one, conforming to the same area and shape. Solving a logical riddle that is the key of the ritual, each layer must keep the same shape and area of the contiguous ones, but using a different configuration of bricks. Finally, the falcon altar must face east, a prelude to the symbolic flight of the reconstructed god towards the rising sun—an example of divine reincarnation by geometric means.

The Agnicayana ritual is described in the Shulba Sutras, composed around 800 BCE in India to record a much older oral tradition. The Shulba Sutras teach the construction of altars of specific geometric forms to secure gifts from the gods: for instance, they suggest that “those who wish to destroy existing and future enemies should construct a fire-altar in the form of a rhombus.” The complex falcon shape of the Agnicayana evolved gradually from a schematic composition of only seven squares. In the Vedic tradition, it is said that the Rishi vital spirits created seven square-shaped Purusha (cosmic entities, or persons) that together composed a single body, and it was from this form that Prajapati emerged once again. While art historian Wilhelm Worringer argued in 1907 that primordial art was born in the abstract line found in cave graffiti, one may assume that the artistic gesture also emerged through the composing of segments and fractions, introducing forms and geometric techniques of growing complexity. In his studies of Vedic mathematics, Italian mathematician Paolo Zellini has discovered that the Agnicayana ritual was used to transmit techniques of geometric approximation and incremental growth—in other words, algorithmic techniques—comparable to the modern calculus of Leibniz and Newton. Agnicayana is among the most ancient documented rituals still practiced today in India, and a primordial example of algorithmic culture.

But how can we define a ritual as ancient as the Agnicayana as algorithmic? To many, it may appear an act of cultural appropriation to read ancient cultures through the paradigm of the latest technologies. Nevertheless, claiming that abstract techniques of knowledge and artificial metalanguages belong uniquely to the modern industrial West is not only historically inaccurate but also an act and one of implicit epistemic colonialism towards cultures of other places and other times. The French mathematician Jean-Luc Chabert has noted that “algorithms have been around since the beginning of time and existed well before a special word had been coined to describe them. Algorithms are simply a set of step by step instructions, to be carried out quite mechanically, so as to achieve some desired result.” Today some may see algorithms as a recent technological innovation implementing abstract mathematical principles. On the contrary, algorithms are among the most ancient and material practices, predating many human tools and all modern machines:

Algorithms are not confined to mathematics … The Babylonians used them for deciding points of law, Latin teachers used them to get the grammar right, and they have been used in all cultures for predicting the future, for deciding medical treatment, or for preparing food … We therefore speak of recipes, rules, techniques, processes, procedures, methods, etc., using the same word to apply to different situations. The Chinese, for example, use the word shu (meaning rule, process or stratagem) both for mathematics and in martial arts … In the end, the term algorithm has come to mean any process of systematic calculation, that is a process that could be carried out automatically. Today, principally because of the influence of computing, the idea of finiteness has entered into the meaning of algorithm as an essential element, distinguishing it from vaguer notions such as process, method or technique.

Before the consolidation of mathematics and geometry, ancient civilizations were already big machines of social segmentation that marked human bodies and territories with abstractions that remained, and continue to remain, operative for millennia. Drawing also on the work of historian Lewis Mumford, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari offered a list of such old techniques of abstraction and social segmentation: “tattooing, excising, incising, carving, scarifying, mutilating, encircling, and initiating.”9 Numbers were already components of the “primitive abstract machines” of social segmentation and territorialization that would make human culture emerge: the first recorded census, for instance, took place around 3800 BCE in Mesopotamia. Logical forms that were made out of social ones, numbers materially emerged through labor and rituals, discipline and power, marking and repetition.